I’m an LA apologist. I like the outdoor cinema at the Hollywood cemetery. I like the Egyptian interiors of the La Vista on Sunset Boulevard and the bus that takes 2.5 hours to get from Silverlake to Westwood. I like the Museum of Jurassic Technology that I desperately wanted to enter but could not because it contained live birds, of which I am deathly afraid. I like Gjusta Bakery and the skate bowls at Venice Beach and the driverless tram that takes you up to the Getty Museum like a scene from ‘The Incredibles’. I like the neon signs for psychics and healers. I like the relentless monotony of the weather, because when you’re on holiday it’s nice for a place that’s not your home to feel utterly alien. I like that one day I ate nothing and the next I ate three meals before noon. I like the pink evening sunlight that falls democratically on every rooftop in the dwarfed skyline.

Laid over the top of this real-time scenery are images my brain has plucked from the collective Californian imagination: Joan Didion’s house parties on Franklin Avenue in The White Album, Humphrey Bogart as Philip Marlowe smoking in the shadow of Venetian blinds, the Sofia Coppola movie Somewhere. Double exposure like this is possible in LA, a place that is bizarrely so much more imaginative than other places I have been, unapologetically superficial, a stinky mixture of dreams and scuzziness, somehow more honest in its embrace of fame and ambition than other centres of civilisation that try to hide it. City of angels, yes, fallen and otherwise.

For this reason, while I was there, I allowed myself to indulge in a micro-cycle of recent non-fiction meditating on self-absorption. What arguably started with Lauren Oyler’s character assassination of Jia Tolentino in the LRB (which then elicited a counter-cancellation attempt of Oyler by Ann Manov in Bookforum earlier this year), reached Australian shores with this piece by Laura Elizabeth Woollett on Bri Lee’s new novel. Soon after, Mark Bo Chu interviewed Oyler in To Be magazine where she spoke about it all again, and Tavi Gevinson released a free autofiction zine about the narrator’s parasocial and then actual and then faded friendship with Taylor Swift. I shouldn’t buy so hard into the drama but it’s hard not to in America: the land that prizes competition and ego but also celebrates the risk and vulnerability that must accompany such shamelessness. Jealousy, gossip, obsession, self-interest, privacy, performance, criticism, a bald watchfulness that feels both crude and honest; those felt like very LA things to me. For the handful of hours I was there, I wanted to simmer in the grand Tinsel-Town tradition of trash talk and judgement.

But my comeuppance was due. As I made my way to LAX, a woman at the bus stop asked me where I was from and where I was going. She was full of unsolicited information about public transport routes and dangerous parts of town. I asked her how she lived in LA without a car and she told me she simply didn’t go very far. In return, she eyed my carry-on suitcase and asked how I could possibly fit a week’s worth of clothes plus all my skincare into such a small bag.

I don’t use much skincare, I replied. She snorted.

–That’ll catch up to you.

And in that moment, the passive aggression hanging in the highway air between us, I realised I was glad to be going home. The frankness I admired as a spectator had finally punctured my safe tourism. LA had caught up to me.

Here are three books that allowed me to extend the California dreaming long after I had left US airspace (not including All Fours, which I bought at Skylight with the express intention of reviewing it here but then didn’t like it that much so didn’t??).

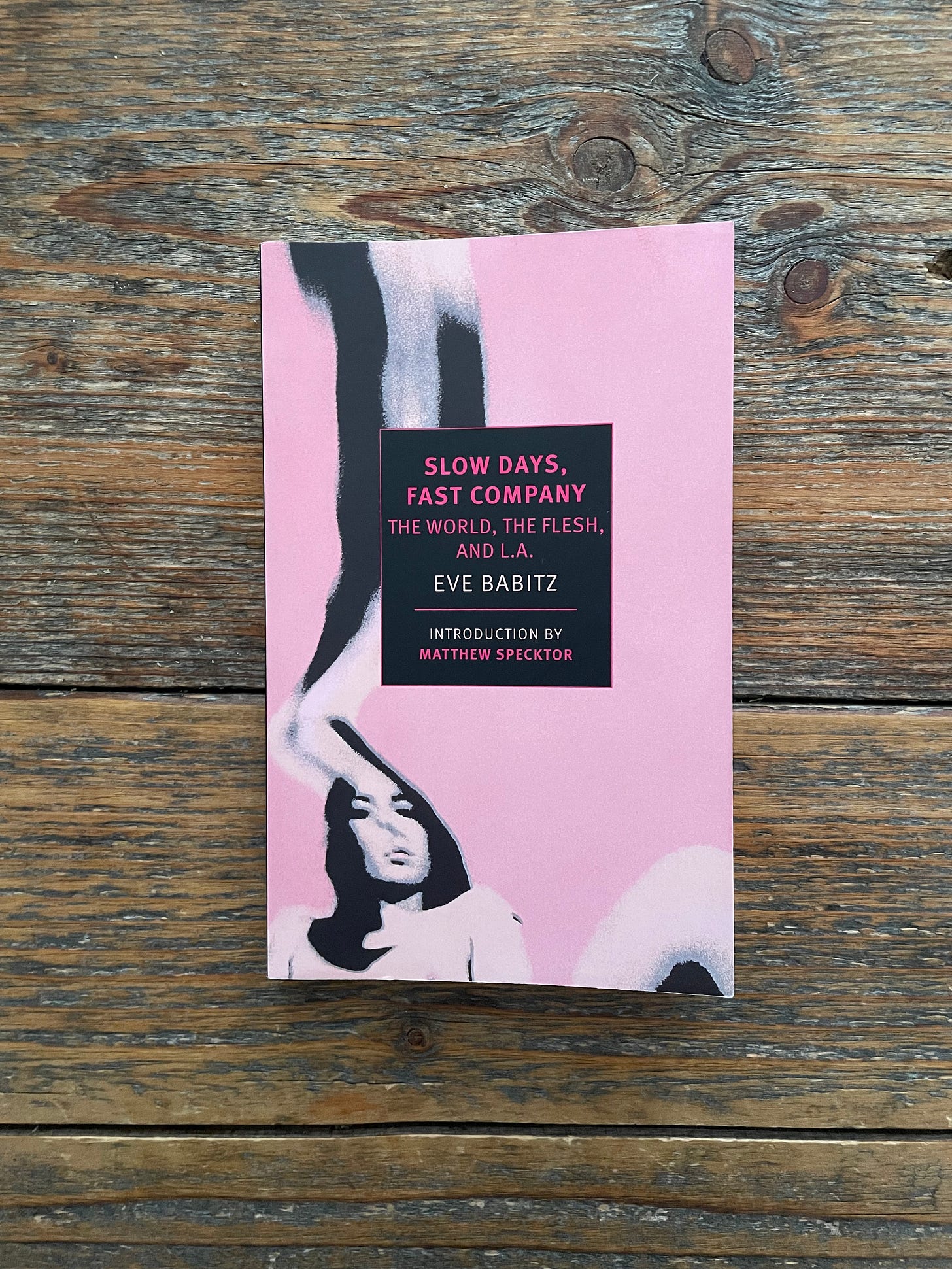

Slow Days, Fast Company by Eve Babitz, 1977

If you want it to rain then wash your car, says Eve Babitz. If you want to give the impression of smugness then tell people you prefer LA to New York, says me. I’d know because I do and I tell anyone who will listen.

I have probably bored you before, also, with the genius of Eve Babitz. But too bad, I’m going to again. Her second essay collection (and probably her masterpiece) is about being a woman/person/artist in the 70s, in a Los Angeles that is equally glamorous and earthy. In Babitz’s LA, the Santa Ana winds make you crazy with desire and one can get sucked into a second bender at the Chateau Marmont even when you’re on your way out the door of the first. Babitz is so deeply of her time and place, but not moored to it when it comes to her literary truth. An essay about travelling to a ranch in Bakersfield with a fan of hers is actually about the porous boundary between home and escape; or a braid of tales about Terry Finch, Janis Joplin, Musso & Frank’s Grill and heroin is in fact about the way “success” is a misnomer for self-worth. Her love of LA, its beauty and its rancour, coats every essay to the point where Eve herself seems interchangeable with the city: restless, beautiful, obvious, shifting, harsh. She loves the place she grew up in because she respects herself; but she also loves the place she grew up in because she wants to be loved in return.

Babitz is an excellent judge of detail. Her descriptions are unexpected but intuitive and her prose is uncomplicated but precise. She is not elegant or controlled the way Joan Didion is (with whom she had a long-standing friendship and rivalry) but she is glamorous, and she is honest in a way that sometimes Didion is not. California girls, they’re undeniable!

My theory is that Eve learned a lot about writing from the rock and rollers she hung out with. She has a knack for dramatic scenery distilled into singular detail; she knows the emotional pulse of every story; and she can create an image early in an essay, bury it and then bring it around again as a neat metaphor at the end. She creates small mythologies within each essay.

I’ll leave you with this quote, which is actually about writing but seems like an excellent metaphor for life in general:

No one likes to be confronted with a bunch of disparate details that God only knows what they mean. I can’t get a thread to go through to the end and make a straightforward novel. I can’t keep everything in my lap, or stop rising flurries of sudden blind meaning. But perhaps if the details are all put together, a certain pulse and sense of place will emerge, and the integrity of empty space with occasional figures in the landscape can be understood at leisure and in full, no matter how fast the company.

There There by Tommy Orange, 2018

A disclaimer up front: this book is set in Oakland, not LA. Hence why I used the term ‘California imaginary’ in the introduction. Sneaky.

Freshly-minted Booker longlister Tommy Orange is Native American and his novel gravitates around twelve Native American protagonists, all intertwined (some related, some not) and living in present-day Oakland. All are, in some way or another, grappling with their cultural identities and the intergenerational trauma of being First Nations in modern America. But all are chiefly concerned with an upcoming pow-wow, of which they are each involved, for either benevolent or nefarious reasons.

As the characters whirl towards the pow-wow (and each other) increasingly quickly, the novel takes the shape of a tornado, wide at the top and then tightening as it gets further towards the earth, whizzing and sucking with centrifugal force. Considering how many characters there are – and therefore how many lives and voices there are to care about — the reading experience was tight and stimulating, like the G-force on a carnival ride; eyes wide, pages turning, the world in constant motion while you are pinned to a wall as a witness. If I was to give a pull quote for the cover it would be: “Electrifying”.

(Naturally, I also loved its cameo in illustrator John Derian’s Georgian-era Cape Cod home.)

Less Than Zero by Bret Easton Ellis, 1985

There’s garden-variety gore and then there is genuine shock at the baseness of human depravity. Bret Easton Ellis trades in the latter. I had no interest in reading Ellis until 2021, when a friend recommended a podcast that fundamentally changed my opinion of him as an artist. Now, I have space for him. I am curious about his read on the cultural temperature. I totally back his 2011 analysis of an age of “post-empire”. And now I have read Less Than Zero, his debut novel written when he was just 21.

Rich-kid Clay is home for the summer from his East Coast college and spends his holidays driving aimlessly around LA. He flits from house party to house party in Bel Air mansions, watching with detached boredom as his peers shoot heroin and become hospitalised for anorexia. He hits a coyote and watches it die, he sits through stilted country club lunches with his film executive father, he fraternises with people called Death and Spit. It’s like Clueless if it came from the Upside Down, the dark twin that was kept in the basement all its life finally coming up for air. As its title implies, the novel shows the nihilism that comes with decadence. I wasn’t alive in the 80s but I can imagine that was a dominant vibe: capitalism as a violence to the soul.

I was genuinely confronted by the last 50 pages and I tread cautiously using the word “recommend” when talking about this book. I want people to know what they’re in for. But luckily, (or perhaps that is the point) Ellis is a skilled enough writer that his technique outweighs the horrific content: the language is so brisk and controlled that I managed to absorb most of the shocking scenes without the secondhand trauma. Unlike the characters, the narrator doesn’t dwell on scenes of horror. Somehow, straight reportage of brutality is easier to digest. The prose does not reward a perverse or twisted reader. But hey, maybe that’s you.