#7: Give 'em the old razzle dazzle

August 2021

In the UK there are two brothers: Cosmo and Merlin Sheldrake. I am lightly besotted with this sibling duo, firstly for their names and secondly for their interests. The former is a musician who plays support acts for Johnny Flynn and occasionally dresses up as a sunflower, and the latter is a scientist who wrote a book about mushrooms.

This gripping mycological enquiry (titled Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds, and Shape Our Futures) charts every fungus-related experience in Merlin’s obsession, from experiments with human-ingested hallucinogens to mycelium packaging startups in Silicon Valley.

His tales are spine-tingling. It turns out separate networks of glow-in-the-dark mushrooms can communicate through electromagnetic waves - a Swedish scientist named Stefan Olsson proved it by growing two separate cultures and filming their growth for a week on a timelapse video camera. Once he had inspected the footage, he watched a wave of bioluminescence pass from the edge of one network to the other. Twenty-four hours later, an identical wave passed through the second disconnected mycelial sprawl. Simply supernatural!

The idea that intelligence exists indiscriminately across all organisms is not a novel notion. But to prove dedication to his thesis of hyper-connectivity between all organic matter, Merlin arrives at an extreme conclusion. ‘Fungi might make mushrooms, but first they must unmake something else,’ he writes in the epilogue. ‘Now that this book is made, I can hand it over to fungi to unmake.’ He dampens a copy of his own book and seeds it with Pleurotus mycelium. Once the network had chomped through the pages and sprouted oyster mushrooms, Merlin ate them.

A sound ecologist named Michael Prime recorded the fungi devouring the pages using electrodes that detect bioelectric activity. Cosmo Sheldrake then transformed the captured vibrations into a song accompanied by human voice and a double bass. The mushroom symphony is the sonic incarnation of the electrical currents flowing through the growing mycelium network as it digests the pulp.

People do such cool shit with books. Me? I just read them.

Second Place by Rachel Cusk

2021

We are only now beginning to see the aftershocks of the pandemic ripple through our books. It takes about 18 months for a good book to be written, edited, packaged and circulated, so it makes sense that the publishing cycle (much like contact tracers) is running alongside the coronavirus. There is a danger however, that readers are so sick of this ubiquitous experience that we would prefer not to see it reflected in our art. And it makes sense that a writer as giant as Rachel Cusk would be the one to tackle such an omniscience.

A family shelters in place at their home on a remote marshland in the United Kingdom, somewhere far enough away that you have to board a boat to get there. The narrator’s name is M, a writer, and she spends her spring lockdown at the house with her partner Tony (a very tall, quiet man), her daughter (who is home from college) and her daughter’s boyfriend (a lanky soft-boi who reads aloud for two hours from the fantasy novel he has been writing for weeks). M writes to a famous artist inviting him to stay, and he arrives with an ethereal and forthright woman named Brett to stay in a peripheral dwelling on the property: the second place.

Inspired by the dreadful time DH Lawrence spent staying at Mabel Dodge Luhan’s artist colony in New Mexico in 1932, Cusk’s painter character (denoted by M as ‘L’) embarks on a treacherous mission of psychological destruction. Made claustrophobic by the pressure of lockdown, the makeshift brood begins to fracture - non-familial relationships seem stronger than biological ones, some characters become more legible as the fury of stasis percolates, and others simply disappear. The distance of their remote location seems to be counteracted with the intensity of human company. How much emotional turbulence can a home take before it ceases to be a sanctuary? Can the domestic space withstand the duress of hospitality? You’ll see.

The Edible Woman by Margaret Atwood

1969

I like to cast my vegetarianism as a facet of my politics (it’s called ecofeminism), but that is both boring and earnest. So instead I’ll recommend a book that swiftly disposes of it.

When Marian MacAlpin accepts her longtime boyfriend’s proposal, she loses her appetite completely. Peter is dreary and marriage seems dull, so her food takes up a vociferous retaliation: steaks shriek when cut into, a carrot she is peeling is skinned alive. It seems that betrothal is something Marian simply cannot stomach. As she whiles away the days at her call-centre job, watching as her colleagues are plucked out by suitors and the ones left behind compete garishly for the scraps, Marian’s mind starts to splinter. The narratorial voice shifts from first to third person as her subjectivity starts to flake away. From this distance, Marian begins to substitute action for meaning: having an affair with a grimy proto-emo and spectating as her hyperfertile roommate cons the local sleaze into sowing his wild oats inside her ready womb (for this companion’s motives, the sire is expendable).

‘She was afraid she was losing her shape, spreading out, not being able to contain herself any longer, beginning (that would be the worst of it all) to talk a lot, to tell everybody, to cry,’ she thinks to herself. Marian’s inability to eat mirrors the autonomy she will relinquish if she marries. If she goes ahead with the engagement, the institution will consume her. To eat or be eaten, that is the question.

Friends & Dark Shapes by Kavita Bedford

2021

Prediction: meandering millennials deflated by the state of the world will be the dominant character trope to emerge from the age of climate anxiety. The young characters in this novel move into a sharehouse in Redfern together and crest and wane with the palpitations of life. They crash gallery openings and get tipsy on free booze, cry at Mardi Gras, and argue about the ethics of hiring a cleaner so that the housework isn’t unfairly weighted towards those housemates with higher hygiene standards (ie. the women).

This book seems like it’s authored by someone who feels like their art-making is an indulgence so tries to shoehorn political potency into a narrative. It’s a bit obvious, is what I’m saying, but the imagery is powerful enough to overshadow the less convincing plot points. I long to walk through Kavita’s streets sticky with the smell of frangipanis and Moreton Bay figs. I love the city of Sydney for its uncity-ness, its obligatory wheezy presence that bows knowingly to the real reason anyone is there at all: the eastern beaches.

The nameless narrator has just lost her father and makes money from freelance journalism, a haphazard vocation that allows her to traverse from one side of the spidery metropolis to the other. Her train rides become observation trips where she can lose herself imagining the city’s characters. The whole book reads a bit like a writer who received a grant to write about ~life~ in contemporary Sydney (read: heavy on scenery but light on insights), but hey, who am I to begrudge someone that? Considering the pitiful state of remuneration for art in this country, can’t blame a girl for trying.

Real Estate by Deborah Levy

2021

The narrator of this electric, elliptical book is Deborah Levy but it’s also not Deborah Levy. How annoying but also truly brilliant. It’s the third in her ‘living autobiography’ series, which started with her childhood in South Africa under apartheid where her father was interred as a political prisoner, and continued through her early writing career and the disintegration of her marriage. This final volume is a culmination of all the energy she’s spent ruminating on these parts of life.

In Real Estate, Deborah-not-Deborah lives in her London flat with an e-bike, a pair of antique wooden carousel horses and the smells of her daughters who have both left for university. Her ex-husband exists but we don’t really know where. Through her writing residency in Montmartre to her sixtieth birthday party at Silencio (the Parisian nightclub owned by David Lynch) to eating guava ice cream with sea salt and chilli flakes and attending glamorous literary parties as a ‘late bloomer’, she dreams of a house of her own.

‘I think it’s so important, what women want,’ she says in a recent podcast interview. She goes on to immediately destablise the association of material possession with the base capitalist project of greed. ‘What they discard and what they bequeath is so important. I have never undermined the domestic in any of my books. How does one become a subject and not an object? How can I embody and disembody a female presence moving forward in the world?’

Deborah goes through these same ethical quandaries, swaying between the opposing positions of owning a zone to the detriment of others and the power that comes with having a room of one’s own (a divorced woman is, after all, unpropertied). She desperately wants to have a property; one with an orangery like James Baldwin’s farmhouse in rural France and filled with her own belongings. She longs to be the architect of a real, comfortable and loving space.

The story takes place in pockets of narrative sewn together with reflection - which is very hard to do - and arrives at few conclusions, which is just the way I like it. Is the mind the only estate we can control? Is our mental geography our own? Does possession make it ‘real’?

As you can tell by this lengthy review, I imagine this will be the best book I read all year.

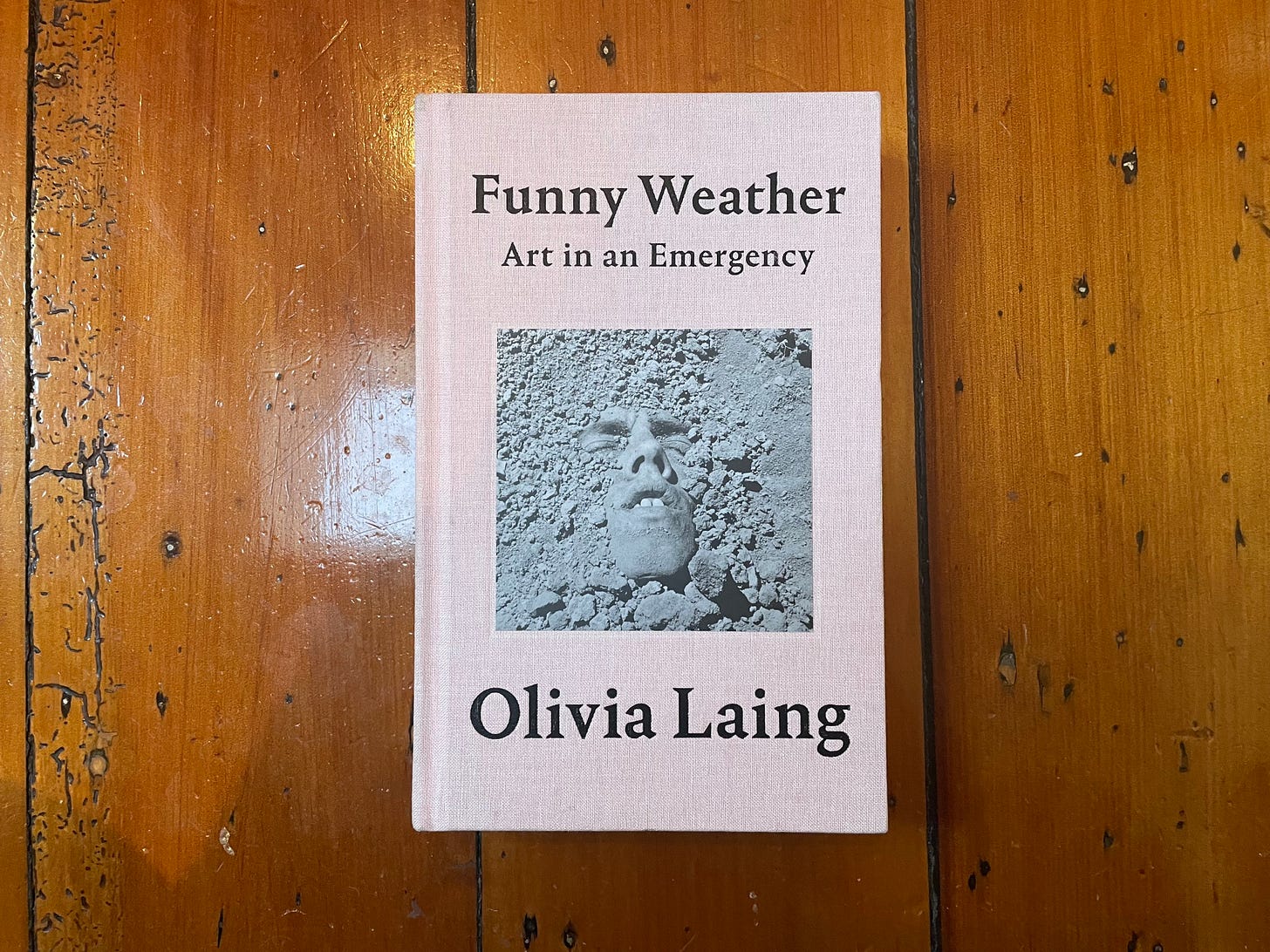

Funny Weather: Art in an Emergency by Olivia Laing

2020

Given writers are the designers of shared imagined worlds, it’s inevitable that they elicit a certain curiosity about their own spaces. What does Maggie Nelson do when she’s at home? Which series does David Hockney’s Netflix algorithm serve him? What does Ali Smith eat for breakfast? The same fascination stirred in me - awake at 12.30am doomscrolling through pictures of Rachel Cusk’s rambling brutalist mansion in Norfolk - is aroused in Olivia Laing, whose artist-focussed criticism is emotional and optimistic.

She is a writer fascinated with the interior lives of creative people, and the way their subjectivities enter their art. Funny Weather gathers the best of her bite-sized artist biographies from the last decade, plus interviews, essays, and columns. Charged with affect and reverence in the places where critics are usually distant and objective, she surveys Deborah Levy, Hilary Mantel, Sally Rooney and others with radical intimacy. It’s an old-fashion mode of criticism - one that privileges the act of art-making as much as the art itself - and positions herself inside each artist’s story. For Olivia, the text is a way to understand its maker as a private self, rather than the other way around. Her body and mind are vessels for interpretation.

In doing so, she proposes an unorthodox mode of engaging with art: to feel and think at once. That rationality must be separate from sentimentalism is a binary feminists have struggled against for centuries. Obviously, emotions can be the engine of thought. What better way to measure if something is good than if you like it or not? Simple as that.

Laing brings her own weather with her wherever she writes, calibrated with subtle emotional shifts. The writing is fluid but so controlled, relaxed and kinetic - it’s like drifting down a river on the crest of a slow current. If The Lonely City was a ripe tonic for the 2020 lockdowns, then Funny Weather will ease your frantic and distracted brain through these ones. Reading it is like spectating a brilliant conversation.

Art in emergency roughly equals panacea in crisis; it’s an anaesthetic with a curative caveat. Given our uncertain times, I’ll leave you with Olivia’s thoughts on reading in the hope it might seduce you further:

'Empathy is not something that happens to us when we read Dickens. It’s work. What art does is provide material which to think: new registers, new paces. After that, friend, it’s up to you.'